In the baseball world, grounders to third, short and second base are called routine plays. Announcers say it, coaches say it, parents say it. They look pretty simple, don’t they? A ball is hit at average speed, the fielder is only 90-110 feet from the batter. The throw across is anywhere from 50 to 130 feet away. These should be outs!

In the baseball world, grounders to third, short and second base are called routine plays. Announcers say it, coaches say it, parents say it. They look pretty simple, don’t they? A ball is hit at average speed, the fielder is only 90-110 feet from the batter. The throw across is anywhere from 50 to 130 feet away. These should be outs!

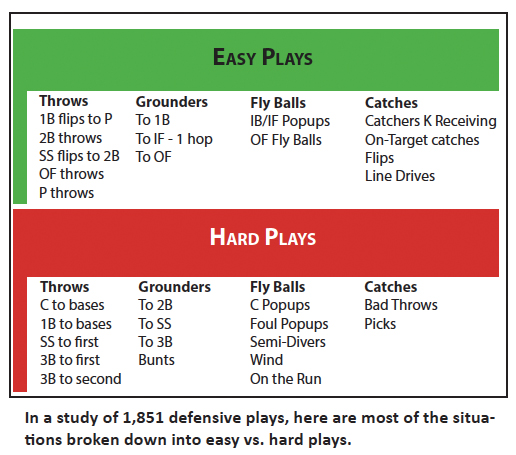

The irony, though, is that these are the exact opposite of routine plays. These are the hardest plays in baseball. We ascribe the term hard plays to divers and long sprints – certainly these are hard plays too, but in the documentation of baseball, these are not considered errors. The official definition of an error is a play that should be made with ordinary effort. Diving plays and balls on the run are inherently extraordinary effort, thus, while exciting and nice, they are not errors.

Ordinary plays are where all the errors are. These are the plays that define teams – “make the plays you’re supposed to make.” And so, the player feels the pressure the most on these – despite them being the most difficult. The pressure a player feels on these plays certainly inhibits performance. Additionally, players (and coaches) don’t practice these “hard plays” enough to be commensurate with the need to work on them.

Think about it: For a grounder, the fielder has to read the speed, read the hop, charge and breakdown correctly, catch the ball while moving towards first, shuffle and make a balanced throw of 50-130 feet to a target about 7 feet by 7 – and do it quickly to beat a runner. Oh, and the first baseman has to catch the ball with his foot on the bag, and sometimes off-line or in the dirt. This is hard.

Other hard plays consist of picking balls in the dirt at all kinds of bases, fielding bunts in thick grass while contorting your body to make a good throw, as well as plays that factor in the wind, the sun, the dust, the spin of balls. These are hard (see the graph above).

Other hard plays consist of picking balls in the dirt at all kinds of bases, fielding bunts in thick grass while contorting your body to make a good throw, as well as plays that factor in the wind, the sun, the dust, the spin of balls. These are hard (see the graph above).

Good defensive teams look to the statistic of fielding percentage to define their defense. Certainly this is a limiting stat, as it doesn’t factor in range factor and probability of making plays. However, this is still a useful stat to help your team improve their fielding.

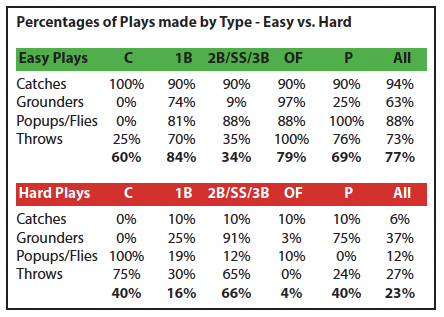

In looking at the percentages of easy plays vs. hard plays, we learn that even the worst team will probably make 77% of the plays with minimal effort for a .770 fielding percentage. These plays are easy and made all the time. Hard plays consist of the other 23% of the plays. An excellent college defense will field at .970, while .960 is good. We can say a .940 defense or lower is bad. Thus, a .970 fielding team makes 100% of the easy plays (77-for-77) on easy plays), and 87% of hard plays (20-out-of-23). A .960 team makes 83% of the hard plays (19-out-of-23). A bad defense makes 74% of hard plays (16-out-of-23).

Thus, if you really look at only the hard plays, great defenses make about 9-out-of-10 of the hard plays (app. 90%), good defense make 8-out-of 10 (app. 80%), while bad defenses make about 7-out-of-10 plays (app. 70%). They all make 77% of the plays, but what are they doing on the “hard plays?” And thus, the difference between bad and great defensive teams are these hard plays, which ironically we call “routine plays.”

Thus, if you really look at only the hard plays, great defenses make about 9-out-of-10 of the hard plays (app. 90%), good defense make 8-out-of 10 (app. 80%), while bad defenses make about 7-out-of-10 plays (app. 70%). They all make 77% of the plays, but what are they doing on the “hard plays?” And thus, the difference between bad and great defensive teams are these hard plays, which ironically we call “routine plays.”

Where all the hard plays?

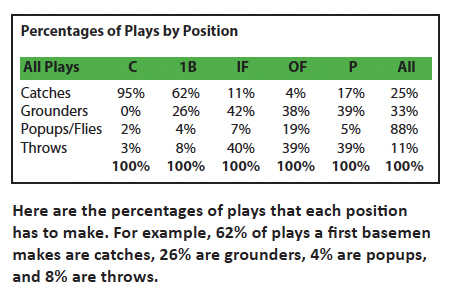

This chart shows percentage of plays made by type. For example, only 9% of all grounders are easy plays by infielders, 100% by outfielders. Thus, infielders need to practice grounders way more than outfielders (why do outfielders get the same amount of grounders in infield/outfield as infielders?). You can also see the most demanding positions: Infielders have the most hard plays (66%), followed by catchers (40%), then first baseman (16%), then outfielders (2%)

So what can we glean from this?

Plays, like routine grounders, bunts, and throws in the dirt, are actually very hard, and the difference between good and bad defensive teams. The margins are small, but they are all the difference. It’s not the highlight-reel plays, but the ordinary plays. The time spent in practice and philosophically should reflect the quantity of occurrence in games, and in turn, can help players cultivate the skills of being truly great at A) catching grounders, B) throws, and C) throwing to a target. That’s it. This simplifies the focus of what to work on, and hopefully can improve defensive play.